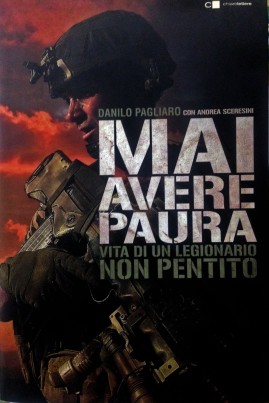

It was published in January and after a month only, it was already at its third edition. The book written by Danilo Pagliaro, a Legionnaire still in service, turned out to be a publishing sensation. This is also because it tells us about a reality, the French Foreign Legion, which is almost unknown in Italy.

Before reading “Never be afraid” I knew nothing about the Foreign Legion. Actually, I had not even ever wondered what it was until my brother put the book into my hands.

In order to discover something more about it, I decide to go to France and to get to know the author. I meet Danilo in Aubagne, in Provence, on a windy and cold day. The appointment is at Le Florentine, a restaurant overlooking the pretty town square. When I enter, I find out that we are not alone: Danilo is surrounded by friends and admirers. Among them there is Riccardo, fond of the Foreign Legion, but far too old to enrol (the age limit is 40 years old). Then there is Silvio, French origin, but Friulian by adoption, with an ancestor in the Légion Étrangère, as they call it here. Sitting at the table, there is also a Trentino family, intrigued by the book; they came to France on the occasion of the commemoration of the Battle of Camerone.

Besides all of this, Danilo is a humble and modest person: he does not like pinning his value medals on his uniform and, when he speaks of himself, he says he is “just a little brigadier-chef”. He is not full of himself, but just as a joke because Danilo, in spite of the image you may have of a legionnaire, is a sparkling wit and playful guy.

After twenty-three years of service in the Foreign Legion and a few months before his retirement, Danilo made up his mind to write “Never be afraid. A not-regretful legionnaire’s life” (published by Chiare Lettere), a text that, in addition to being a sort of autobiography, includes information on recruitment practices and an appendix with the list of Legion regiments and traditions.

“This book was born to dispel the dozens of messages I receive on ‘Military Forum’, the largest unofficial Italian military forum, where I bumped into people saying huge, stupid things about the Foreign Legion. They talk about us as bloodthirsty killers who torture and kill for money. Do not even mention it! All nonsense: the Legion has never been this stuff here!” He explains, impatient with the bad legends and fibs that circulate about it “It is obvious that when you go to the assault it is necessary to kill, but in the same way as the French army, the Italian one, or any and every army. Writing ‘Never be afraid’ was also an excuse to talk, through my story, about nowadays society.

In particular, it is to Italy, to his country, that Danilo addressed harsh criticism: “a united nation only when the national football team wins. In that very case, everybody waves Italian flags! And I do not care if there are people who will treat me unsympathetic for what I say: this is the reality!” says Danilo, who did not mince nor chew his words “I’m not exposing my ideas. I am not saying: ‘Italians are good or bad people’. What I say is just the truth, seen from the outside, from a person who has not been living in Italy for years”.

Inevitably, we end up talking about the decline of civil society (and the armed forces, which “are the mirror of society”), suffering from what Danilo in his book called “intoxication of doing good”, an attitude that leads to laxity in every sector. And he would point out that one of the main problems is that “everyone is talking about rights, but no one thinks of duties”. A society where everything must be strictly, politically correct and “that has simply lost the instinct for survival. When your only interest is to have fun, eat, drink and spend, that’s when decline begins”.

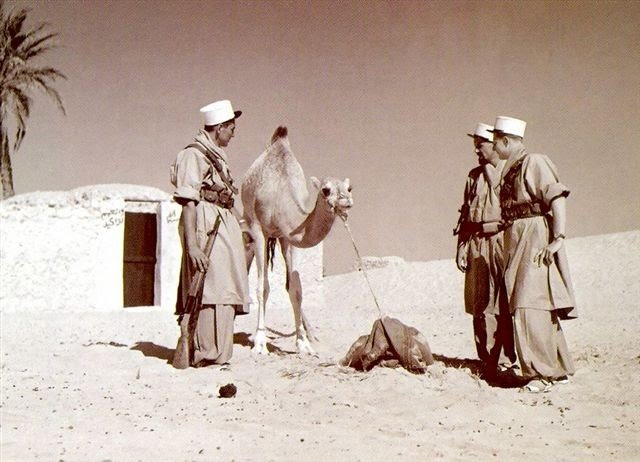

Coming to France to know Danilo and talk about his book, I took the opportunity to attend the ceremony of the Camerone Battle, ritual held every 30 April in the barracks of the Foreign Legion in memory of one of the most incredible battles of world military history. Taking place in 1863 in Camarón, Mexico, it dealt with a bunch of sixty legionnaires who managed to stand up to about two thousand Mexican patriots and accomplished the assigned mission.

Capitain Danjou’s wooden hand, Museum of Foreign Legion, AubagneAs far as this year’s parade is concerned, in the barracks in Carnoux en Provence, it was necessary to involve some legionnaires of the Thirteenth Demi-brigade (which is normally instance in the UAE, but it is now being transferred to France) to fill the parade file. “It’s a very special time: we have men elsewhere”, explains Danilo who guides us through the Museum of the Foreign Legion in Aubagne. It is in here that some historical relics are preserved as symbolic items. Among these, Captain Jean Danjou’s wooden hand, one of the Camerone legionaries and Lieutenant Colonel Rollet’s red umbrella, which was always kept up during the battles, as a reference point for the soldiers who were going to attack him.

After the ceremony, we go to eat all together, friends, admirers and journalists, in Cassis where Danilo answers the questions I intend to ask him about the Legion and “Never be afraid”.

In the first part of the book, that of your youth, you offer us a restless Danilo in search of his place in the world. You describe yourself as a guy who wants to “do something useful for others.” Moved by these values, you try and enrol thus joining the Police and with the outbreak of the Gulf War, you try to volunteer in the Navy in order to leave for the Middle East. This desire of yours to do something useful, you’re finally able to satisfy it in the Legion, aren’t you?

Absolutely right; because here there is an incredible group of professional people going all in the same direction. We call it “family”, and rightly so. We do not “go to war”, as some think, but we intervene when there is a real crisis. I do not remember having tortured, but I remember we did an operation where we have saved 2.200 people that would have otherwise been killed by machetes. Yes, I remember this. Or operations where we rescued some nuns who were crying because they did not think they would see the next day. I remember this. On those occasions you find yourself face to face with people you have pulled out of hell: you put them in the armoured vehicle, then you take off for hell, but they are safe now, they are out of hell. It is fabulous and makes you feel accomplished. This repays you, not the salary.

AQIM (Al Qaeda in the Maghreb) in Algeria, Mali, Senegal and Ivory Coast. Boko Haram in Nigeria, Cameroon and Chad. Al Shabab in the Horn of Africa. And then Oqba bin Nafa in Tunisia, ISIS in Libya, where it has now taken root, and the Islamic State of Sinai in Egypt. The jihadist bite in Africa is shifting its focus on the “black continent”. At the moment, France is engaged in the Sahel with the Barkhane operation. According to you, who have worked extensively in Africa, the situation is really so bad as it seems, or have the conflict protagonists just changed?

Africa is in a situation that cannot get worse. Once upon a time they killed for a specific purpose, today they kill for another. The reasons have changed, but there is a more complex problem at the bottom, a problem that affects not only the economic reality, but also the mentality and culture of those countries.

Danilo Pagliaro

The veterans and the disabled represent a topical issue in the United States where the soldiers, returning from the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, did not find a structured recovery program. Indeed, often, the only thing they found was the public opinion indifference. 44% of the veterans of the last decade have difficulties in entering and re-integrating civilian life as well as looking for a job. A number of men who took part in these wars get back home with psychological problems that are aggravated because they are not being looked after: post-traumatic stress disorder which results in suicide (according to the Department of Veterans Affairs an average of 18 a day) and in episodes of violence involving civilians.

Why do you think these boys come back home with injuries? Is there a flaw in the selection methods, in the aptitude test or the training program that does not prepare soldiers to the psychological pressure of the war?

No. As a matter of fact, we do have the same problems in the Legion. The difference is that we are 7500, so if we have 10% of our people who have problems, the amount comes to about 700 people. In America, they have an army of 300.000 soldiers, and that means that if the percentage of soldiers with psychological trauma is at 10%, the number of individuals suffering from stress is 30.000. That’s why we know that the Americans have these problems while you think that it does not apply to us. It’s just a matter of numbers. In short, you have to understand that we are humane and we are afraid just like anybody else! We are simply outnumbered. In addition, we represent France, which actually does not take part in all the wars in the world: despite what is said, we are not in contact with certain situations, alike the Americans.

In France there are two shelters for those who have served in the Légion. “The Légion is a family” happens to be one of your mottos. Consequently, all of those who have served remain framed in some way in a participatory context, and are not forgotten nor left on their own.

Exactly. We do not swear on the Republic: we are not French. We swear on principles. One of the seven points of our honour code reads: “Never abandon neither your dead, nor your wounded nor your weapons”. When a person comes out because he retires or has problems, there is a form of aid and assistance. In the Légion there is the BALE, (Bureau des Anciens de la Légion Étrangère) which the legionaries may contact should they come across or face any kind of trouble or difficulty.

What is the most important thing you have learnt in the Légion?

The greatest teaching was: “Never be afraid”. But not in the idiot sense of the exalted people who want to go to the front to “play or act as Rambo”. When at war, everybody fears, of course! What I mean is: “Never be afraid to rise, to start it all over”. If I fall, I will get back on my feet. If I break a leg, I can take care of that. Anyway life goes on. Do not be afraid to believe, to live, to keep walking. The Legion taught me this. It let me experience these teachings, it has taught me that it is possible to live like this. This is the “Never be afraid” I wanted to entitle the book with.