20 February 2016

I was desperate to ask Maurice, my guide, how many people he’d killed but his quiet modesty stopped me

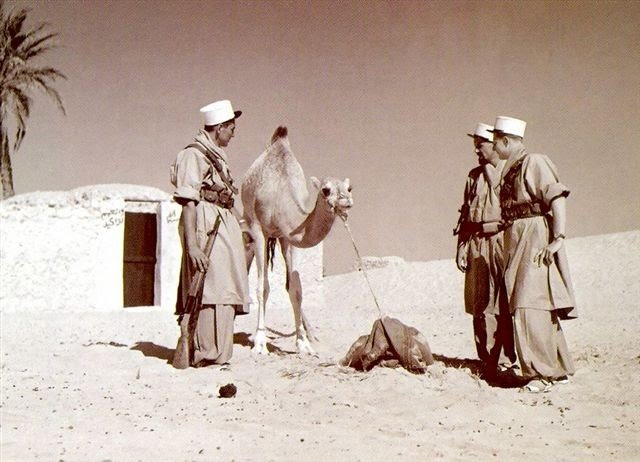

In the Foreign Legion’s Museum of Memory at Aubagne, near Marseilles, I examined the kit, weapons and uniforms from the Legion’s formation in 1831 up to the present day. Uniforms from the Crimea, the Mandingo war, the Mexican expedition,the second Madagascar expedition, the first world war, the Algerian war, the first Gulf war: there they all were, displayed in glass cases. My museum guide was Maurice, a proud Legion veteran. Green Legion tie, natty silver-buttoned regimental waistcoat, close-cropped head and an impressive row of medals on his chest. You only had to look at his lean face to see how fit he was. A tour of duty in the Légion Étrangère is five years. Maurice has five under his regimental turquoise belt.

Next we silently meditated on the prosthetic hand and forearm of Captain Jean Danjou. The fighting spirit of the Légion Étrangère is embodied by this macabre artefact. It is its most sacred possession. Danjou fought in the Crimea, lost the hand fighting in Algeria, and was killed in Camarón in Mexico, where he and his 62 men defended a hacienda against a besieging Mexican army of 2,500 infantry and 500 cavalry. It was France’s Rorke’s Drift. During the battle, Danjou made his exhausted men swear on his wooden hand that they would fight to the last round and the last man. When the ammunition ran out, the six légionnaires left standing fixed bayonets and charged the Mexican army. Three were killed, three captured. The honourable Mexican general applauded this display of French courage by allowing these three to leave the field bearing their arms and the body of their slain commander. Camerone Day, 30 April, is the Foreign Legion’s big commemoration day. Danjou’s prosthetic hand is taken out of its glass case and paraded before the assembled Legion at their Aubagne barracks.

Confronted with the beautifully crafted wooden hand, and the do-or-die courage represented by it, and conscious of Maurice’s quietly scintillating pride, I wanted to say something appropriately reverential. But all I could think of to say to Maurice was, ‘Is there still flogging in the Foreign Legion?’

Maurice regarded me askance, uncertain whether my question was jocular or whether I was an idiot. Here was a man of dignity and pride, whose motto was legio patria nostra — the legion is our fatherland. The Legion is also his family. Every Christmas Day is spent in the barracks with his brothers in arms rather than with his wife and kids. His very bearing was a model of quiet fidelity. Earlier he told me that when he joined, his first best pal was a highly amusing, violent lunatic of an Englishman who eventually ran away. And I think Maurice fondly hoped or imagined that the English are all a bit like that. My stupid question was tolerated. ‘No. No flogging,’ he said. ‘Not for many years.’

Naturally, I was also dying to ask him if he’d killed anyone, and how many, and under what desperate circumstances, and whether it had subsequently preyed on his mind; but Maurice’s bearing somehow forbade it. So I asked him about his medals. He was happy to oblige. This one, he said, pointing to the red one, was the Légion d’honneur, established by Napoleon in 1802. He dismissed it with a flick of the hand, as if it were an annoying fly. ‘Brigitte Bardot has this,’ he said. ‘She has this for showing her ass.’ The yellow and green one, however, was a different kettle of fish and you could tell he was proud of it. The Médaille militaire is awarded for meritorious service or valour in action, and is the highest French military decoration. ‘You got it for valour?’ I said. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘In the Pacific.’ I am very sorry to say that the impenetrable barriers of his modesty and to a certain extent the French language prevented my unearthing of further details.

Afterwards we went for lunch at L’institution des invalides de la Légion étrangères at Puyloubier, a beautiful château and vineyard home to 85 Legion veterans ‘of good character’, who earn their keep tending the vines and working in the bookbinding and ceramics workshops. In a homely upstairs restaurant, we were served an excellent plain meal of fish and boiled potatoes by gentle, aged, decrepit Legion veterans, and I drank a glass of their red wine. Through the window the rows of leafless vines stretched away towards the uncanny limestone peak of the Montagne Sainte-Victoire that so obsessed Cézanne. And our simple meal was frequently interrupted by a succession of ancient légionnaires of every nationality who came to the table to greet and embrace Maurice with a quiet, dignified love that passed all understanding of this lifelong civilian, but which nevertheless impressed him enormously.