6/12/2006 • World War II

At first the intelligence officers at the headquarters of the French Foreign Legion in Sidi Bel Abbès, Algeria, were puzzled. The Legion had always had a large complement of Germans in its ranks, but now, in spite of the Nazis’ widespread campaign to discourage Germans from enlisting, even larger numbers were pouring in.

In the late 1930s, as more and more young Germans were joining that famous fighting force, the German press was violently attacking it, and the Nazi government demanded that recruiting be stopped. Books about the Legion were publicly burned in Germany, and the violence against Legion recruiting reached comic heights when Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels’ department claimed that innocent young Germans were being hypnotized into joining. In 1938, a professional hypnotist named Albert Zagula was actually arrested in Karlsruhe and charged with the offense.

Still the Germans kept joining–until half the privates and 80 percent of the noncommissioned officers in the Legion were German. Eventually, it became evident that this influx had been orchestrated by German intelligence, the Abwehr, to destroy the Legion from within. The new German legionnaires came close to achieving the Abwehr‘s objective.

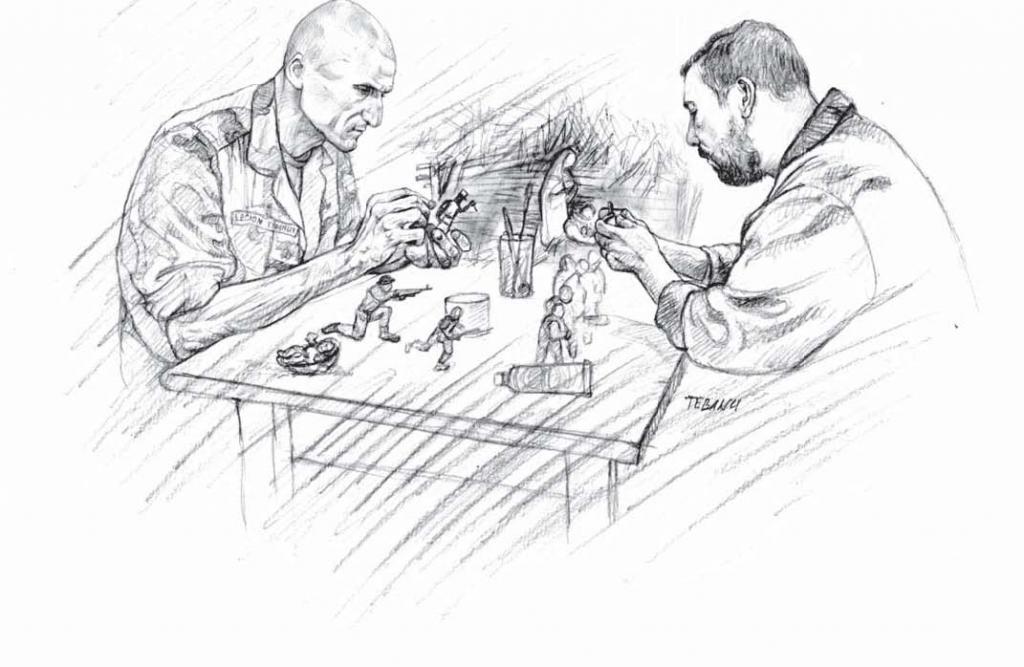

The French Foreign Legion had always attracted the dispossessed of every land, and in the 1930s there were plenty of refugees throughout Europe. First there were Spaniards, the losers in that country’s civil war; then there were the Jews and others fleeing Nazi persecution; later, Czechs and Poles were added to the list as the German army began its march across Europe. These recruits did not mix well with the new Germans in the Legion. The German noncommissioned officers terrorized the non-Germans under their charge. There were frequent fights and courts-martial. The officers could not trust their own noncommissioned officers. Morale in the Legion plummeted, and there was even some talk of disbanding the entire corps.

When war was declared in 1939, the situation was critical. To ease the problem, large numbers of German legionnaires were shipped off to desert outposts, and the ranks were filled with additional non-German refugees. But the French authorities still thought that there were too many Germans in the ranks, many possibly loyal Nazis, to risk sending the Legion to fight in Europe. Instead, four more foreign regiments were raised in France and trained by veteran Legion officers from North Africa. These legionnaires garrisoned the Maginot Line, the string of concrete fortresses that the French had built as their main defense against Germany. There, they remained inactive during the so-called ‘phony war, when neither the Allies nor the Germans took any serious offensive action.

In spite of the general reluctance to send entire Legion units to France, the French authorities decided that something had to be done with those loyal elements of the Legion that were still marking time in North Africa and itching for a fight. In early 1940, the old Legion was given an active role. Volunteers were called for, and two battalions of 1,000 men each were assembled–one in Fez, Morocco, and the other in Sidi Bel Abbès. Volunteers for those units were carefully screened, and the only Germans left them were veteran Legionnaires of unquestioned loyalty. Those men were given new non-German names and false identity papers to protect them in case they were captured by the Germans.

The two battalions were joined into the 13th Demi-Brigade (13e Demi-Brigade de la Legion Etrangere) and put under the command of Lt. Col. Magrin-Vernerey, one of those military eccentrics who so often turned up in the Foreign Legion, a hard-bitten graduate of St. Cyr and a veteran of World War I. As a result of wounds received in World War I, he had physical disabilities that should long since have disqualified him from service. Severe head wounds had been crudely operated on and left him with a nasty temper, and surgery on a smashed limb had shortened one leg, causing a noticeable limp. But he was a fighter, and that was all the Legion wanted.

When the 13th Demi-Brigade arrived in France, the always-blasé legionnaires showed no surprise when they were issued a strange new type of uniform–and skis. Those veterans of the desert sands were being trained to fight in Arctic snows and outfitted as mountain troops with heavy parkas, boots and snow capes. They were bound for Finland, where the Allies were aiding the Finns in their fight against the invading Soviets, who were at that time in league with the Germans. But before the Legion left France, the Finns bowed to the overwhelming power of the Soviets and accepted the enemy’s terms. The war in Finland was over.

But there was another fight. Winston Churchill, then Britain’s first lord of the Admiralty, had urged the mining of the waters around neutral Norway, where the German navy was escorting convoys of iron ore shipped from neutral Sweden to supply the German war machine. At the same time, Adolf Hitler had decided that the Germans must seize Norway, not only to protect the ore shipments but as a naval base for surface raiders and U-boats. Soon fierce sea battles raged between the Royal Navy and the Kreigsmarine, and at sea the British had the upper hand.

Strong British land forces were also shipped to Norway, but the Germans invaded the country. By April 1940, the Germans had occupied all of the main Norwegian west coast ports–from Narvik in the north to Kristiansand in the south and around the tip of the peninsula to Oslo, the capital. British and Norwegian forces fought hard, but without success. The British were ordered to evacuate Norway.

The Allies had one more card to play. Although they had to abandon southern Norway, the Allies would attempt to wrest the northern port of Narvik from the Germans to prevent ore shipment. An amphibious assault was planned under the overall command of British Lt. Gen. Claude Auchinleck, with the protective guns of the Royal Navy and using mainly French and Polish troops. A key part of this force would be the 13th Demi-Brigade.

When his subordinates asked why the 13th Demi-Brigade was going to Norway, Magrin-Verneret’s oft-quoted reply was typical of the legionnaires’ ours-is-not-to-reason-why attitude. Why? My orders are to take Narvik. Why Narvik? For the iron ore, for the anchovies, for the Norwegians? I haven’t the faintest idea.

The 13th Demi-Brigade was part of a task force called the 1st Light Division, which was commanded by French General Marie Emile Béthouart. The force also included units of the French 27th Chasseurs Alpins and the Polish 1st Carpathian Demi-Brigade, a mountain corps made up of refugees from conquered Poland. There were also many Norwegian units in the area still able to fight.

The plan was to sail up the series of fjords that led to the port of Narvik under the protection of the Royal Navy, which still controlled the Norwegian Sea. The 13th Demi-Brigade was to strike directly at Narvik, with its flanks guarded by the French and Polish mountain troops and the Norwegians.

Opposing the legionnaires was the German garrison under General Edouard Dietl, reinforced by the 137th Gebirgsjager regiment, a veteran mountain unit hastily drilled as paratroopers and dropped into the snow-covered hills. These tough, well-trained mountain troops were as proud of their edelweiss insignia as the Legion was of its seven-flamed grenade. They would be hard to crack.

Before the 13th Demi-Brigade could attack Narvik itself, the nearby village of Bjerkvik had to be taken, for the high ground behind it dominated the strategic port. On May 13, the 13th Demi-Brigade was landed on the Bjerkvik beaches. At midnight, the big guns of the British battleship Resolution, the cruisers Effingham and Vindictive and five destroyers opened up on the German defenders. Shortly thereafter, the advance troops hit the beaches in infantry and tank landing craft. It was the first time in the war that such combined operations took place in the face of enemy fire.

The German reaction was severe. At first light, the Luftwaffe came out, bombing and strafing the ships and beaches. The Legion pushed on in the face of artillery and small-arms fire. Colonel Magrin-Verneret waded ashore, encouraging his legionnaires forward. For a while it was touch and go. Captain Dmitri Amilakvari, a 16-year Legion veteran who was to take a key hill, was held up by furious German fire. Then, shouting A moi la Legion! (the Legion’s traditional version of follow me) to his men, he charged up the slope. The Germans fell back before the savagery of the attack, and the hill was taken. Amilakvari pushed on to Elvenes where he met up with the Chasseurs Alpins on his flank. Bjerkvik, now a smoking ruin, and the surrounding mountains fell to the French.

Then the Legion turned its attention to Narvik itself. In a repeat of the Bjerkvik attack, the port was bombarded from the sea while Allied troops poured over the surrounding mountains. Once again the Luftwaffe appeared and bombed the attacking warships, but Royal Air Force Hawker Hurricane fighters arrived on the scene in the nick of time and cleared the sky of German aircraft. On May 28, the 13th Demi-Brigade marched into Narvik and found the town deserted. The Germans had fled.

For the next few days, the legionnaires pursued the retreating enemy through the snow-covered mountains toward the Swedish border in sub-zero temperatures. Their aim was to capture Dietl and what was left of his troops or force them over the border into Swedish internment. They were just 10 miles from Sweden when they were ordered to return to France. A few weeks earlier the Germans had begun their invasion of the Low Countries, and the phony war was over. All the troops and equipment in Norway were needed in the defense of France. The 13th Demi-Brigade embarked for Brest happy with its victory, the first Allied success of the war, but disgusted that it had not been permitted to finish the job.

Meanwhile, those hastily raised Foreign Legion regiments at the Maginot Line were getting a baptism of fire. Much has been written of the defeat of the French army in 1940, but little is heard of the heroism of many of its beleagured units. One of those heroic units was the 11th Foreign Legion Infantry (REI). The regiment was a cadre of tough legionnaires from North Africa and recent foreign volunteers enlisted in Europe, reinforced by a battalion of unwilling French draftees. The Frenchmen disliked being thrown in with the infamous Foreign Legion, and the result was not pleasant.

In training during the phony war period there was much drunkenness, fighting and courts-martial, but when the German panzers broke through in May, the dissension among the 11th REI’s elements disappeared. While other French regiments were caught up in the panic, turned tail and ran before the overwhelming terror of the German tanks and Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers, the 11th REI stood firm. During two weeks of hard fighting, they held off their attackers while other French units retreated around them. Finally, almost totally surrounded, they were forced to fall back. Colonel Jean-Baptiste Robert burned the regimental standard and buried its tassel, which was later dug up and returned to the Legion. There were only 450 men of the original 3,000 left to return to North Africa with the 11th REI after the armistice.

The 97th Foreign Legion Divisional Reconnaissance Group (GERD 97) also attained glory during the 1940 debacle. It was probably the only all-veteran North African outfit of the Legion regiments in France. GERD 97 had been organized from the 1st Foreign Legion Cavalry Regiment, the Legion horse cavalry outfit that had been raised in Africa in the 1920s from the remnants of White Russian General Baron Pyotr Wrangel’s cavalry, which had been all but destroyed in the civil war against the Bolsheviks. Mechanized and outfitted with obsolete armored cars, GERD 97 carried out reconnaissance missions, but its scouting days came to an end when it ran into the powerful German Mark III tanks. In typical Legion style, GERD 97 threw itself against those monsters without hesitation, fighting rear-guard actions to cover the retreating French. GERD 97 managed to survive until June 9, when a final, suicidal charge against the panzers left all the Legion vehicles burning. There were no known survivors.

The 13th Demi-Brigade returned to France from Norway, sailing into the harbor at Brest on June 13, almost at the same time the Germans were marching into Paris. Colonel Magrin-Verneret was ordered to form a line as part of the proposed last-ditch Breton Redoubt, but it was no use. The Germans had broken through.

While on a forward reconnaissance mission to determine what could be done to delay the enemy, Magrin-Verneret and some of his officers became separated from the main body of the 13th Demi-Brigade, and when they returned to Brest they could not find any trace of the unit. The reconnaissance party assumed that the main body had been over-run, and the colonel determined that he and his companions should try to get to England, where the British planned to fight on. Every boat seemed to have been taken over by fleeing British and French troops, but the Legion officers finally found a launch that took them to Southampton. Miraculously, most of the 13th Demi-Brigade had already found a way to get there.

On June 18 General Charles de Gaulle, now himself a refugee in England, announced: France has lost a battle, but France has not lost the war! Magrin-Verneret immediately offered the services of the 13th Demi-Brigade to the new Free French movement, and soon they were in training at Trentham Park Camp near Stoke-on-Trent.

On June 25, the FrenchGermanItalian armistice was signed. The men of the 13th Demi-Brigade were given a choice: fight on with de Gaulle, or return to North Africa, which was now under the control of Marshal Henri Philippe Petain’s newly formed Vichy government. The 1st Battalion, strongly influenced by Captain Amilakvari, elected to stay with de Gaulle. The 2nd Battalion went back to Morocco and was disbanded.

The French Foreign Legion, like the rest of the French empire, was now sharply divided. The 13th Demi-Brigade had given its allegiance to the Free French, while the rest of the Legion, scattered throughout North Africa, Syria and Indochina, remained under the thumb of the Vichy government, which meant being under the sharp watch of the German Armistice Commission.

The Germans demanded that the men they had planted in the Legion be returned to the Reich, and the Legion was not sorry to see them go. But the commission had other, not so welcome demands. They had lists of refugee Jews, Germans, Poles, Czechs, Italians and others who they wanted back, to send to concentration camps.

There were many men in the French army in North Africa, particularly in the Legion, who had no sympathy for the Vichy government and hated the Germans. Besides, the Legion had a reputation for taking care of its own. Its intelligence system usually discovered the Armistice Commission’s visits well in advance and knew the names of the legionnaires on the lists. The wanted legionnaires were given with new names, new papers and new identity discs. When the Germans came too close, the refugees would be transferred to far-off Saharan outposts where the commission seldom took the trouble to visit.

Part of the armistice agreement required that French forces surrender all but the most basic weapons. The Legion defied this order and buried or otherwise secreted in remote areas much of its more useful materiel. Many of the Legion’s officers and men in North Africa would have liked to join de Gaulle’s forces, but outright desertion did not appeal to them and surrounding mountains and desert prevented them from reaching the Free French in any great numbers. The Legion units in North Africa simply had to bide their time.

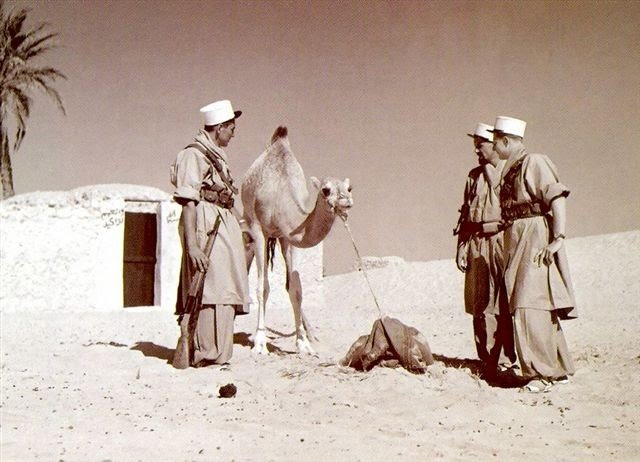

The two elements of the Legion even took on a different appearance. The main body in North Africa still wore the French army prewar uniform–a baggy tunic and breeches with ancient roll puttees–while the Free French wore British-style battle dress or tropical shorts, plus occasional odds and ends left over from the Norwegian campaign. Both Vichy and Free French Legionnaires wore the traditional white kepi of the Legion and displayed its grenade insignia.

The Vichy Legion in North Africa was not only constantly harassed by the Armistice Commission but was short of weapons, gasoline and sometimes even food and tobacco. Legion strength fell to less than 10,000 men, and the Germans continually urged the Vichy authorities to disband it altogether. Morale was at rock bottom, and the rate of desertions and suicides was rising. The 13th Demi-Brigade, on the other hand, was refitted, and new members were added to its ranks.

The 13th Demi-Brigade’s first adventure with de Gaulle was a failure. A battalion under Dmitri Amilakvari, now a lieutenant colonel, left Britain on June 28 bound for Dakar, the principal port of French West Africa. It was part of a large convoy escorted by British and French warships, and the battalion was on the same headquarters ship as de Gaulle himself.

The French general’s plan was to talk this important colony into supporting the Free French cause and becoming the base for all future operations. But de Gaulle had miscalculated. The governor general of the colony, Pierre Boisson, was loyal to the Vichy government, and a brief but violent naval engagement ensued. Not wanting to risk his ground troops, of which the Legion battalion was a major part, de Gaulle decided not to try an amphibious assault on the heavily fortified port. Bitterly disappointed, he ordered the convoy to sail down the African coast to Douala in the Cameroons, which was already on the Free French side.

For months, the 13th Demi-Brigade marked time in the Cameroons while the Allied authorities decided where to send it next. Then in December, the two battalions– reunited under Colonel Magrin-Verneret, now called Colonel Monclar–left on a long sea journey around the Cape of Good Hope, up the east coast of Africa and into the Red Sea. On January 14, the Legionnaires disembarked at Port Sudan, then British territory. A rail trip took them into the desert where they were to prepare to serve as an adjunct to the main British force in an attack on Italian Eritrea. Just south of the Sudan, Eritrea was mostly stark desert. Lieutenant John F. Halsey, an American newly commissioned in the Legion, described the days of training that followed. Sand and heat nagged and plagued us. The air was hot and dry and the sun was merciless. It burned and scorched necks and the exposed skin between the bottoms of shorts and the tops of socks. It glared on desert sand, on the rocky shale bare of vegetation, on the hills. There was no shade.

That was how it appeared to a new officer, but to many of the Legion veterans, it seemed like old times. Halsey noted that his men broke into cliques and gathered in circles on the sand at various halts, stretching out, apparently unmindful of the sun and sand. They bore up under the training easily. Had Halsey been with the Legion longer, perhaps he would not have been so surprised.

The Eritrean campaign turned out to be a triumph for the 13th Demi-Brigade, but not an easy one. The first Italians they met–in the mountains around Keren–were tough, determined Alpini who resisted the legionnaires with skill and courage. It took several days of hard fighting before the Italians broke and surrendered in large numbers. The Legion seized nearly 1,000 prisoners.

After the battle at Keren, the Legion was off to Massawa, the chief Red Sea port of Eritrea and the last principal city in the country to hold out against the Allies. The outskirts of Massawa were protected by a series of fortifications, dominated by Fort Victor Emanuele. After British artillery heavily bombarded the fort, the 13th Demi-Brigade was ordered to take it. First, the legionnaires had to clean out–with bayonet and grenade–Italian machine-gun emplacements in the surrounding hills. Then they scaled the walls of the fort. When the legionnaires gained the fort the defenders, who up to that point had resisted fiercely, lost heart and surrendered. On the afternoon of April 10, 1941, Colonel Monclar and two truckloads of legionnaires entered Massawa. Eritrea was now wholly in Allied hands.

After the French army was routed in the Battle of France, the Allies had been somewhat skeptical of the abilities of some French military units. After Keren and Massawa, that attitude changed, and when the situation in Syria became serious, the British did not hesitate to seek the aid of French troops. Syria and Lebanon, the lands known as the Levant, had been under French mandate since World War I. The British had tried to avoid any armed conflict with the Vichy forces that controlled the region. Those forces had variously been estimated at between 35,000 and 80,000 strong, all under the command of General Henri Dentz. Among those forces was the 6th REI, the tough, desert-hardened Foreign Legion regiment that had garrisoned Syria for many years.

The Levant was of extreme strategic importance. German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was threatening Egypt from the west, and if German forces penetrated the Levant, the Suez Canal and the Middle East, with its vital oil, would be menaced. The Germans were demanding the use of ports and airfields in Syria and Lebanon, and the Vichy French were complying. The Allies could not tolerate this. On Sunday, June 8, 1941, a hastily assembled Allied force of about four divisions crossed the Palestine and Jordan borders into Syria. The polyglot army, including British, Australian and Indian troops and a Jewish contingent from Palestine, was later joined by the Free French.

The French complement was itself a colorful mixture. Centered around the 13th Demi-Brigade, it was composed of French Marine infantry, Senegalese Tirailleurs, North African spahis and a cavalry unit of Cherkesses. The latter were refugee Circassian Muslims who in past years had fled from czarist persecution and settled in Syria. Led by Frenchmen, they had deserted the Vichy authorities en masse, crossed into Jordan and joined the Free French forces. Dressed in colorful Cossacklike uniforms, they were expert horsemen and fierce fighters.

As he had at Dakar, de Gaulle hoped that the Vichy regime in Syria would turn its coat and join the Free French, but it was not to be. Dentz obeyed his orders from Vichy France and resisted the invasion. The battle for Syria was sad for all the French forces, but particularly so for the soldiers of the Foreign Legion. Not only was it Frenchman against Frenchman, but in the case of the 13th Demi-Brigade, it was the Free French Legion against the Vichy Legion. For a military unit whose motto was Legio Nostra Patria, the Legion is our country, it was a family fight.

The Free French Legionnaires crossed into Syria from Palestine in the only transport that could be scraped together, a bunch of rickety civilian trucks, cars and buses that kept breaking down at various inopportune moments. The 13th Demi-Brigade, along with elements of the 7th Australian Division, was given the objective of taking Damascus. The march was similar in many ways to the Eritrean experience. Suffocating heat, blowing sand, burning sun, shortages of water all made the march sheer hell–the Legion was in its element.

After several days in the desert, the 13th Demi-Brigade reached the hilly country near Damascus, where the fighting began in earnest. The Legion had no air support and no anti-aircraft artillery, and Vichy French planes took a heavy toll. The Legion was bereft of any effective anti-tank weapons, and it appeared they would be overrun by the Vichy tanks, but at the last moment Free French World War I-vintage 75mm artillery came to the rescue, firing point-blank and destroying the tanks.

Furious infantry fighting erupted all along the line as the Legion slowly advanced toward Damascus. On the outskirts of the city, the 13th Demi-Brigade met its brother legionnaires of the Vichy 6th REI face to face. The 13th Demi-Brigade hesitated–were the other legionnaires friends or enemies? They stared at each other for what seemed to be a very long time. Finally, the 13th sent out a patrol. As it approached the Vichy outpost, the Vichys turned out a guard who smartly presented arms–then took the patrol prisoner!

It was a typically Legionlike gesture, a demonstration of respect from one legionnaire to another. It was also the signal to begin the fight, and attack was followed by counterattack, bayonet charge by grenade assault. In the end, the Vichyites were overpowered, and the 6th REI fell back. On July 21, the 13th Demi-Brigade, battered, bloody and exhausted, marched into Damascus in triumph.

There was more heavy fighting before all the Vichy forces in the Levant capitulated. An armistice, signed on July 14, gave the Vichy troops the opportunity to join the Free French. About 1,000 survivors of the 6th Regiment came over to the 13th Demi-Brigade, enough to form a third battalion. The dead of both sides were buried together. That battle was the end of the division in the Legion that had begun with the Nazi infiltration just before the war. The Syrian affair was the last time the Legion was at war with itself.

Legion units made a token resistance to the American invasion of North Africa in November 1942, but they soon turned about and marched against the Germans in Tunisia. By that time, the 13th Demi-Brigade had joined the British Eighth Army to defeat the Axis forces and chase Rommel out of Egypt and across North Africa.

Rearmed and equipped by the U.S. Army, Legion units fought the Germans in Tunisia, Italy and France. By war’s end, the triumphant notes of the Boudin, the Legion’s marching song, could be heard from the banks of the Danube to the French Alps.