https://archive.spectator.co.uk/

22 AUGUST 1940 By P. 0. LAPIS

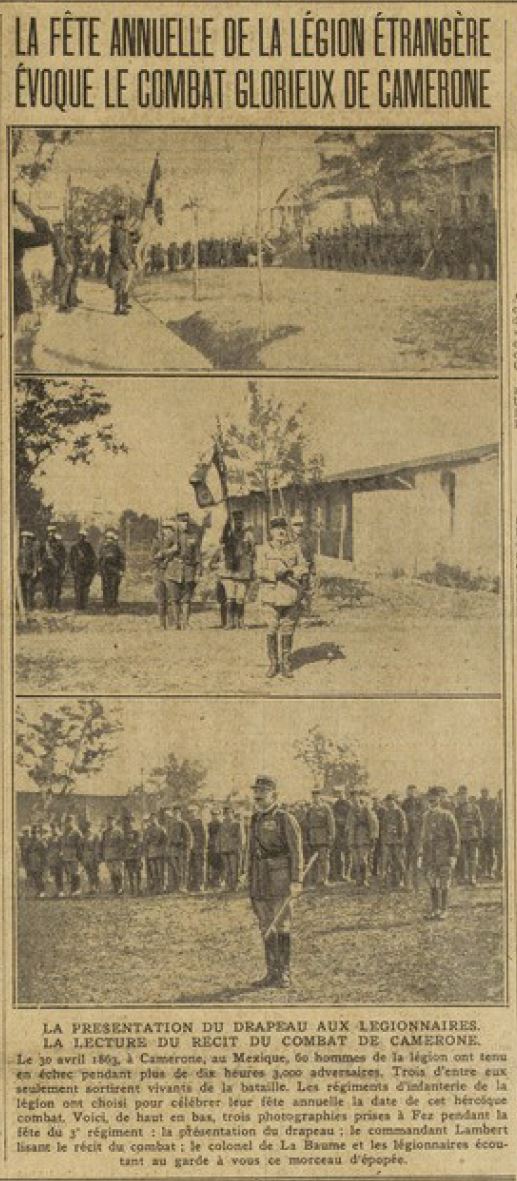

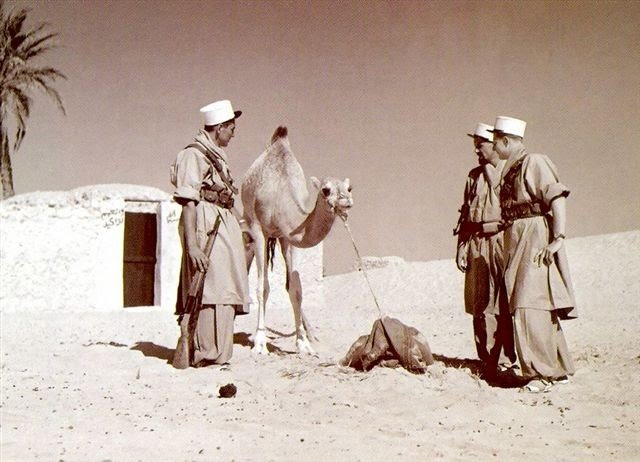

MUCH has been written, in many places and in many tongues, about the Foreign Legion, and I might add that all sorts of things have been said about it. My own experience of the Legion was not long, but it was profound because I was able to live the life of the legionary where it should be lived— on the battle-ground. Crisis reveals character; fighting proves the soldier.

It was during the Norwegian campaign that I became an officer in the Foreign Legion. Most of my friends of that period are in England now. In their training at the camp, they still evince the same will to fight which they showed in the many battles that made them the conquerors of Narvik, and which will reveal itself anew in further campaigns at the side of the British troops. I recently asked permission to spend a week- end at the camp and we relived our memories and talked of life, but as often happened during the campaign itself, the conver- sation took a somewhat philosophic turn. What, we asked each other, is the spirit of the Foreign Legion? We had discussed that already in Norway.

Most of the officers were French. Captain Francois de Luzancay, who was killed during the bombardment of Bjerkvik, was the son of an aristocratic colonel from Vendee. The colonel came from the Franche Comte. Others had been born in various parts of France, and had homes, families, small estates in Berry or in Brittany. Some had been through the military college of St. Cyr. Others had begun their military careers as leg:onaries and had worked their way up from rank to rank until they became lieutenants, perhaps after twenty years' service. Among the foreign-born officers it was the same—some, who had been officers in a foreign army, retained their foreign rank, others had worked their way up from the ranks. One, a Georgian prince, tall, fair, with simple manners and a haughty voice, directed his machine-guns with consummate tactical art, and when bullets from the other side made a hole in his cloak and almost grazed his throat, he brushed them aside with his hand; he was, and remained, a prince. Another had been through all the internal campaigns in Germany, from Bavaria to the Baltic, chased from lakes to the forests, and from pla'ns to the mountains, sometimes wearying of the ideals which failed him, one after another, but always fresh for battle. One came from the East, another from Scandinavia.

It was the army of Gideon. The colonel, who liked to quote Scripture, often pointed out that Gideon, when he was forming his army, put aside those who lapped the water like dogs when he sent them down to the lake, and kept those who carried the water to their mouths in their hands. This colonel had written a book on the morale of infantry during battle—a book that the General Staff had preferred not to see published. We agreed that detachment, a kind of asceticism, was the basis of an officer's calling. What we had left behind—and, I might add, what was before us—was necessarily of no account. Perfect men of action, my comrades lived between the past and the future, at the very instant of the present.

The professional army, and above all the Legion, implies that essential virtue of the soldier, combativeness.

" That seems commonplace," said the colonel, " but not so common as all that. When speaking to the great democratic armies, one always talks of sacrifice. Sacrifice! By so doing, the commanders themselves imply that there is something that the men have to sacrifice. This something is civil life, com- fortable life, wife and children, position, cars, little houses with bay windows, and slippers! Alas, it would appear that the slipper has become the symbol of civilisation and the ideal of life. To sacrifice something so essential, so rare, so precious and so profoundly human as slippers, men must be offered something to counterbalance them: a magical and inspiring goal. Magical and inspiring goals are not to be found every day. But they were found by Cromwell's Ironsides, with their id v0.. of religious freedom, and the armies of the Revolution, with St. Just's idea of liberty—God. If you cannot instil into the troops some similar idea, fame, revenge, the glory of God, or liberty, to outweigh in their heart the love of slippers, you are beaten."

The Legion is warlike because those who come to us have nothing to sacrifice. The legionary has already—often, I admit, for reasons which originally had nothing to do with asceticism but were due to a moral accident in his life—sacrificed his slippers. But he could have started life again elsewhere, in another land if he had had to leave his own, without entering the lists of war. He has chosen the life of camps, and danger. For the Legion's officers it is different. We have our homes, our families, our ties, our affections, but we are men of action. There may be things that are bound to us ; we are certainly not bound to them. We never wear slippers ; either-we wear boots or we go barefoot. The same thing applies to motor- cycle racers, aviators and all professions which entail taking risks. There is no sacrifice because our happiness is in action, dangerous action.

" Look at Lefort," said the colonel, " he is always dreaming of some brilliant deed. Remember Luzancay, we always had to hold him back So much for sacrifice, for the past. And I would say as much for the future. Action is sufficient in itself, without regard to its purpose. I fought in Morocco before the war of 1914. Was it for Lyautey, for the Sultan or for the banks? I fought against the Turks in Cilicia. Was it for the Greeks? I have fought in Poland, in China, and again in the Sahara and Morocco. Why? I never asked why. It was to live to the full.'

Here we were then, in the Norwegian affair. For months and months we had been waiting impatiently in the African sands. As far as the war was concerned, they had forgotten us—the Legion. We groaned. Suddenly they discovered us and sent us from the tropics to the Pole. What joy, what enthusiasm! At last we were going to see some fighting, we who had taken no part in this war, we should have the conqueror's halo. But no, hardly had we landed, on the morn- ing of our first battle, when we learnt of the invasion of Belgium and Holland. The great offensive had begun. Far from being the capital event, we should be only a side-show of the war. an anecdote in the epic. Did this prevent us from fighting? Not at all. We fought, and we retook Narvik in less than a day, when they had been hesitating outside it for two months. There was hard fighting in the mountains, after which they made us retreat. Narvik was certainly taken; but Paris was about to fall. So we had fought in vain, without glory, without even success. Did anyone grumble? Who would grumble at a fight? For a warrior, there is no vain battle.

This is the real military spirit. This soldierly mind, this spirit of the sword, is, above all, that of the Legion. With the other sate of mind, the spirit of the slipper, regiments can be made, but they are regiments of electors. Cr else these crowds have to be inflamed with the burning spirit of revolutions; the free God of Cromwell, the liberty God of St. Just, or what has beaten us for the moment, the devouring myth of Hitler.